At this point, it should come as no suprise that Susan Thackrey's writing is without fail

always pitch perfect (see, for instance, her Listening Chamber edition,

Empty Gate, for pacing, balance, pitch, timing), and yet, I'm always astonished by how effortlessly she hones in on what's at issue. I realize now, after finishing her epilogue for Susan Gevirtz's

Aerodrome Orion & Starry Messenger, that I should have let her do the talking for both of us from the outset. After reading Thackrey's brilliant Oppen Lecture (of which I recently found extra copies in O Books storage if anyone's interested ) I have complete faith that she can effortlessly articulate what everyone else is struggling to express. Certainly true here. Here's Thackery in full (with deep respect):

Epilogue. Words said after other words. And how can an epilogue be written after Susan Gevirtz has led and let us into the "sheer territory" that is the literal existence of these poems, territory so diaphanous in its terms of existence that "no flag can plant there." (This read the day before the Democratic Convention, when it was said aloud, that the American flag is still, still planted on the moon). "The grip of the reliable," says the poem of our general situation, is an impossible attempt to get a grip, and "a sad mantle."

In this sheer territory, the poet says, for every traveler in every air plane, "here is traded for here," making every "here" both ubiquitous and a situational fiction, every perceiver who might say "Well

—here we are!" either a confabulator or a liar, or maybe both. The elements of what once might have been a narrative disappear as "here is traded for here." Wasn't the title of the fictional autobiography in Tolkien

Here and Back Again? But what in the name of any sky-god you might care to call upon could the title

Here and Back Again have to say of any imagination of changing place as a mode of transformation?

Time, in these poems, is equally undone. As the poet begins to recite the beginning of one tiny story by Hans Christian Andersen, she writes, "there was once," the almost iconic phrase of beginning imagination, linking time and place

—but she moves it immediately, inevitably, to the phrase "there was a," without naming an object, seeking safety in linking place to thing, if only the thing could be named. But this, too, proves untenable

—so the words of the poet shift into "there was trespass"

—because in this state of being every boundary that shaped a world or a time or even a constellation in the sky is gone.

Neither can personal experience, eyes that see, be trusted, only those other "caffeine-bruised" eyes of the air traffic controllers, staring at the sky-prostheses of their screens, themselves linked to instruments, creating a continuously changing pattern in the sky, filling up the sheer sky invisibly in a way that leads to visible life or death for the passenger.

If words dividing space and time and personal experience have become useless to describe their once separate fields, then cause and effect, even in Hume's sense (or perhaps especially in Hume's sense) that the occurrence of an event at least

seems to follow or be followed by another event that is always, for us humans, so similar as to be predictable

—cause and effect are also impossible words. So Susan's poems set up their own terms

—"cause

is effect." So no one is permitted to return to that field either.

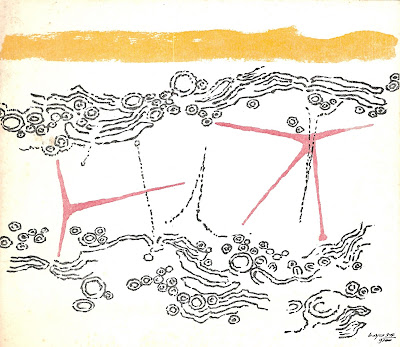

The sky, more depthless and wider than the sea, has been a field of imagination, not of trespass, long before the Pleiades were painted on the wall of Lascaux cave 17,000 years ago. Only 150 years ago Holderlin could call the sky the "eyes blue school" and wander it at will. Now it is a situation, not a field. Now, Susan Gevirtz says, we are always inside it. But hidden within this poetry are notes of other possibilities. Although we

are always inside, an airplane, a language, a set of facts learned too soon, she asks "how many off-screen landing strips get by" the controllers. Fact, she says, can always be outsourced to dreams, and new stars and words can be seen by the "naked eye." Here utter receptivity to the enormous contemporary flummoxing of imagination pre

sents her,

presents, with the present.

A mode of being known to Galileo, known, as he said, and as the poet quotes:

"to no one before the

Author recently perceived them

and decided that they should

be named."

Susan Thackrey

September 2008

San Francisco